Published: Canberra Times, Food and Wine, 2 November 2004

The noodle is the gypsy music of the food world, proving itself a resistant traveller through time, space, conflict and celebration. It significantly pre-dates cocoa cola and the Big Mac as a truly global food, having adapted to new environments, absorbed the influences of available ingredients and condiments, and reinvented itself in diverse forms.

While the noodle, or pasta more generally, is present in nearly every country in the world where rice or wheat is harvested, its origins are yet to be thoroughly documented. Many cookbooks continue to suggest that Marco Polo took pasta from China to the Western World upon return from the Far East in 1295. The late Kenneth Davidson, however, points out in his epic Oxford Companion to Food (1999), that this is one of the world’s greatest culinary myths. In fact, there were many references to the existence of pasta in Italy prior to Polo’s return.

While there is evidence that noodle production flourished in ancient China, other specialist research suggests noodles may have begun their life in Iran. Indeed, one school of thought suggests that noodles was introduced to Italy during the Arab conquests of Sicily, carried in as a dry staple. If the noodle’s origins are in the Middle East, it seems unusual that so little is now consumed in that region. Davidson suggests that it is possible that pilaf in Iran and couscous in North Africa gradually replaced the role of noodles in ancient times.

From China, noodles spread to the cuisines of many other Asian countries including Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore. And the invention of the instant noodle by Nissin Foods in 1958 propelled it to the status of a global phenomenon. Japanese consumers recently rated instant noodles as the country’s most important 20th century invention, just ahead of karaoke.

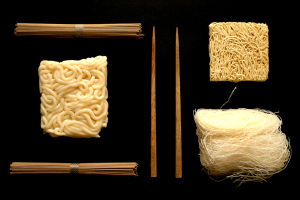

Whatever its origins, noodles boast a number of important social and culinary characteristics. They are easy to store and transport, can be consumed hot or cold, are cheap to produce, are nutritious and filling, and are quickly prepared. They are also diverse in their style and application – having adapted to both varied eating patterns and agricultural production in different countries. Reflecting differences in agricultural production across Asia, noodles can be made of wheat, rice, mung bean, or even yam.

Noodles are slurped from brothy soups such as a Vietnamese pho (rice sheet noodles), a Japanese Tempura Udon (thick slippery wheat noodles), ramen soup (Chinese wheat noodle served in a broth with fish cake and pork slices), or a Malaysian laksa (Hokkien noodles and rice vermicelli). They can be scooped up from the peanuts and prawns on a good plate of Pad Thai (rice stick noodles), slurped from a Brown Sauce – Asia’s take on spaghetti bolognese – or consumed in a beautifully cold form such as soba noodle with soy, shallots, and pickled ginger.

The noodle too has pushed itself beyond these traditional roles as global culinary and cultural boundaries have become more porous. After the end of the second world war, Chinese-style noodles (ramen) became extremely popular in Japan. In the Philippines, the intermingling of Spanish and regional influences are evident in guisado – a popular dish consisting of sauteed noodles with garlic, onions, tomatoes, shrimps, pork and vegetables. And in contemporary Australia, any distinction between European and Asian forms of pasta are ignored in a dish like Tetsuya Wakuda’s angelhair pasta. It is served with asparagus and truffle oil, with an underlying sauce of chicken stock, mirin, soy sauce, and sake.

Which such a remarkable history, it is no surprise that the noodle has played a wider role in social and family life. In Cowra, two hours from Canberra, Anna Wong (Co-owner/Chef at Neila), has fond memories of making noodles in her mother’s kitchen. “The oldies used to get together back in those days when there would have been about one or two Asian shops in China town, and make the noodles together. Noodle making sessions were an important opportunity for family interaction. The traditions were passed down to the children in the family, with secrets of the noodle preparation closely guarded,” she said.

In northern parts of China, many cooks have also preserved the traditional methods of making noodles. Renown Australian food critic, Terry Durack, described in his 1998 book Noodle (Allen and Unwin) an 85-year-old Beijing noodle cook in action. “He effortlessly stretched a soft, white blob of dough into a thick skipping-rope affair which began to dance before my eyes. It twirled and furled and stretched and strained until he deftly passed one end of the dough into his other hand, causing the rope to twist upon itself. Back and forth he folded the rope upon itself until the man produced noodles so fine they could pass through the eye of a needle.”

Four Rivers in Dickson is one of few local restaurants offering home-made noodles. “We are also hoping to bring out a Chef from China in the coming year to make our noodles in the traditional ways,” says owner Peisen Guan. The first Sichuan style Chinese restaurant in Canberra, Four Rivers offers several interesting and high quality noodle dishes. These include a beautifully silky and slippery Sichuan Style Bean Jelly, which is served cold in a Sichuan chilli oil. The noodles are created by scooping a metal implement across the surface of a jelly mould made of mung bean. Another excellent dish is Dan Dan Mian (Dan Dan Noodles) – which translates as ‘pole carrying noodles’ from the days when noodle sellers would carry their produce on shoulder poles. The noodles are served warm in a nutty and beefy stock, of which Chinese sesame paste is an important ingredient.

Those in search of other excellent noodle dishes around town should try the Laksa Lemak at the Dickson Asian Noodle House, Pho at Tu Do in O’Connor, Char Kueh Teow at Timmy’s in Manuka, or a Pad Thai at Lemongrass in Civic. While you slurp away, give a thought to the noodle’s remarkable journey to your plate or saucer.