Australian Photography magazine, January 2004

Long queues, vodka, mafia, rows of grey apartment blocks, permafrost, potatoes and cabbage. When I departed Australia for Russia in 1998, these were common and well-entrenched images held by many in ‘the west’ of the sprawling Moscow metropolis. Upon arrival in the Russian capital, I soon realised the images reinforced in the Australian media could not capture the complexities of the former Soviet Union. Hence, I embarked on a personal journey to inform family and friends of its many contrasting perspectives and illustrate the changes encountered by Russia on its bumpy ride from central planning to the marketplace.

Moscow offers it all to the avid photographer – stunning subject matter, endless adventures, great opportunities for exploring the full range of camera technique, and considerable social and technical challenges. Moscow is huge, pumping, flashy, and full of contradictions. It’s stunning architectural diversity, the remnants of socialist iconography captured in statues and busts, and fairy-tale like churches and domes provide great photographic juxtaposition against against grungy, broken down industrial plants, and a jingle-jangle skyline of construction and cranes. New Russians in expensive foreign four-wheel drive vans carve up the roads, their blue roof-lights giving warning to nearby babushkas collecting empty bottles from the roadside.

composition

While there are many picture-postcard depictions of Russia available on the market, my aim was to create a collection portraying aspects of every day life – to identify objects and institutions that captured the essence of life. The act of simply thinking about the objects or images that could best portray the culture was important, as was maintaining an open mind to new photographic ideas. I identified great photographic potential in institutions such as weddings, weekends at the summer dacha (equivalent of our shack), travelling to and from work, as well as the abstract and common – a russian typewriter, a kettle, a rubbish dumpster, or even an abandoned rustbucket vehicle. While such subject matter was every day for Russians, as an outsider I could spot the photographic potential.

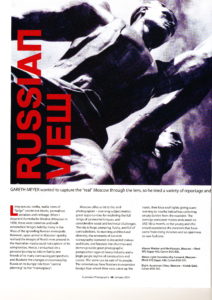

Having decided upon the range of subjects to photography, I employed a range of camera and compositional techniques in assembling my photographic essay. My favourite tools included black and white imagery, saturated colour slide film, camera tilt, multiple exposure, use of blur, and tight cropping of images. Black and white photography, assisted by a deep red filter, emerged as my favourite medium for capturing elements of Russia. The filter intensifies contrast, thereby coaxing incredible light play betwen shadows and strong lines, and enhancing the texture of wooden subjects. It also allowed me to think and compose in black and white terms by removing the colour from the viewing lense. I employed this technique on images of aged timber, such as Peter the Great’s original cabin of the 1700s, in capturing the timelessness and beauty of the Novodevichy Convent in central Moscow, and in drawing out a strong silhouette effect of the fun rides at Gorky Park. I also combined this technique with multiple exposure – a facility now provided within the modern SLR camera. That is, one can simply program the camera to allow up to six shots to be exposed on one negative, thereby removing the job in the darkroom. I found this technique effective in capturing the saturated industrial skyline by the Moscow river, as well as generating an abstract effect with Russian lettering at the Piskarovskoye Cemetry – the buriel place of almost half a million Petersburgers who died during Nazi Germany’s 500-day blockade during the second world or “great patriotic” war.

Russia is generously sprinkled with remnants of the communist era that provide excellent points of contrast for either black and white or colour photography. Many of the headstones and busts of former leaders and Senior Party figures – Lenin, Stalin et al have been removed from central positions of cities and towns and placed in areas such as the Graveyard of Fallen heroes in Moscow. They have strong sharp lines, square jaws and their outreaching hands strive and stretch to meet the limits of cosmos or comanding heights of industry. Drawing inspiration from the Soviet photographic masters like Alexander Rodchenko, I employed camera tilt to accentuate the industriousness and sharp angles of military memorials, and statues of soldiers, tanks and aircraft that sprinkle the outskirts of Moscow. Playing with alternative angles and placing outreached arms of statues into the corners of the composition enhanced the dynamic feeling of the image (see the Worker and Peasant).

These and other subject matter also benefited from another favourite method – that of cropping. In capturing objects or even people, I found that tight cropping or selective photography of one porition of the subject made for much more interesting images. One segment of a wooden house or window pane could speak much more than capturing its entirety – it draws out patterns and lines and askign the viewer to ponder longer on the subject (see Russian Typewriter).

Intense and saturated colour slide film was manadatory for capturing the spectrum of hues created by the Baroque palaces of the 1800s through to the Art Nouveau masterpieces of the turn of the twentieth century. In St.Petersburg, through its many rambling lanes and not far from where Rasputin met his untimely death, I was fortunate to stumble upon a striking image – the sharp and vibrant reflection of a classic Petersburg apartment block on one of its famous canals. While reflection has become almost a cliche of photography, it was rare to stumble upon one of such vitality. Furthermore, I tightened the shot just to cover the building’s image and not the surrounding area of the canal. This created a painting-like effect, capturing one of St.Petersburg’s great dichotomies – the beauty of its many great mansions and yet the need for substantial refurbishment in some areas of the city.

Another technique I employed to generate painting-like photographs was the use of blur on slide film. On a white-knuckled ride down a pothole-plagued track in Siberia, I pounded through endless rows of shimmering birch and pine until the taiga gave way to breath-taking vistas of Lake Baikal. Portaryng a sense of this epic journey, I cropped the camera on a segment of forest – and shot in available light with slow-speed slide film. The absence of a tripod for several thousand kilometres proved to be a .. , as the slight camera shake produced an unexpected and welcomed effect – almost one of impressionism.

challenges

Great photographic opportunities, such as those offered by Russia, also come with great challenges. In Russia, these took a number of forms – extreme climatic and lighting conditions, bureaucracy, secrecy, and vanity. In seeking to capture the essence of a country like Russia, people were always going to be important. As a foreigner, however, the limitations are great. Russians are very proud people who display great warmth and form strong bonds within their own family structures. Quite understandably, they do not, however, share the same familiarity and outward openness to new people or people of foreign nationality. Exploring the back streets of Irkustk, a small township in Eastern Siberia, I came across a babushka who’s life story was told by the thousands of lines and grooves in her aging face. As she clutched her cat to her body, I snuck up and sought her aprpoval for a portrait. “Why? Why? Why would you want to take a photograph of this old and horrible face?” she barked. It is a directness you encounter often in Russia. Fortunately, several blocks away I managed to charm a similarly elderly women – sitting near the bustop on a major thoroughfare, I purchased the several bouquets of flowers, paid a decent sum, and then asked if a quick photograph would be possible. She, thankfully, agreed.

Other Russians have stronger feelings about the appropriateness of photography. While the abundance of military memorabilia makes for retro, soviet-chic images increasingly popular in stylised magazines such as Wallpaper, precautions must be taken. Some of those wonderful buildings adorned by dramatic stars or bass reliefs of tanks, will often be military colleges, academies or ministries. The officials that guard them value their jobs and are immune to the Australian informality and sense of humour, A dose of larrikinism will not go down to well in former closed townships that pepper the vast countryside. As a rule, ask first if you are not sure.

You might also discover a number of additional and unexpected photographic fees while shooting in some locations such as old church grounds, cemeteries or museums – there is little value in fighting higher charges applied to English speaking tourists.

Extreme climatic and lighting confitions also required additional equipment such as spare batteries for sub-zero tempratures, rain-protective filters, fast films and tripods. Short days in the inter, where darkness can extend until 9am and then again at 3.30pm has its limitations. When shooting snow, the additional reflected light could produce underexposed images – requiring the exposure to be overexposed by one or two f-stops to avoid muddy images. When using colour film, the snow tends to produce a blue cast on the final image – although in the case of my shot of a historic village in Suzdal, it can have a positive artistic effect.

My four years in Moscow represented a training period with my first SLR camera – a place for learning how to adapt to all climatic and social conditions that shape photography. You could photograph russia for years and stil be challenged by its elements and by the change it is undergoing.